Illustration - Spring 2013 - Issue 35

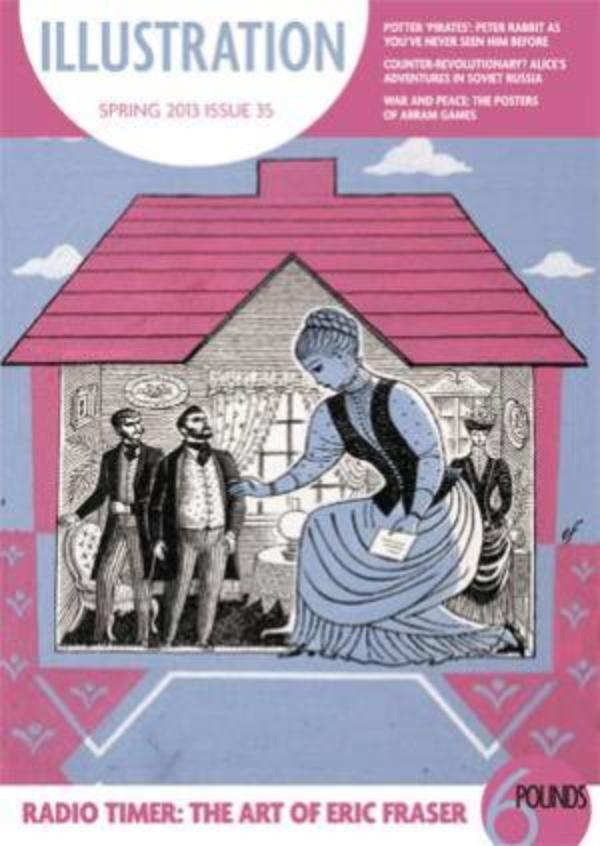

Anyone who thinks illustration is “mere decoration” should perhaps get a wider perspective on the ways in which it can be seen as a force for good or evil. Victorians were keen exponents of the view that “good” art was “improving” – for example, William John Loftie’s A Plea For Art in the House (1876) urges householders to buy art that will be good for their wives, children and servants, both emotionally and morally. In the 1940s Abram Games echoed this with his belief that his illustrations and posters should improve the lot of society. Meanwhile, Eric Fraser was producing illustrations for the Radio Times which, as a BBC publication, made them a part of Lord Reith’s overall ambition to educate, entertain and inform. Other illustrators were hired to support health and safety campaigns, producing characters such as Tufty the road-safety squirrel, who is now coming out of retirement to feature in a new exhibition on propaganda.

Similarly, illustrations can fall foul of the authorities for promoting an undesirable ethos. When Soviet Russia relaxed its tight control over the arts, Russian illustrators brought their experiences of artistic repression and propaganda to the previously banned texts of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, creating unique interpretations of these familiar works. On the other side of the iron curtain, the failure of Frederick Warne to copyright Peter Rabbit in the US meant that American illustrators were free to create their own versions, sometimes with a Wild West look that is a far cry from Beatrix Potter’s Lake District.

The iron curtain gone but, as Michael Johnson found travelling across north Africa, other areas are now viewed with official suspicion and illustrators can show an alternative vision to a global public. There’s nothing wrong with decoration, but if you assume that decorative art has no meaning you may miss something important.